Wood-engraved half-title

Steel-engraved frontispiece to the first volume of The Universal Songster. Published by John Fairburn, Broadway Ludgate Hill. June 11th 1825. Lettered with publication line and artist’s name “Designed & Etched on Steel for the Universal Songster; By George Cruikshank”. The centre of the design shows two seated men (one of whom resembles a Toby Jug caricature) smoking pipes within a decorative foliate frame. The rest of the design depicts ten other characters, including a soldier and a Scotsman, amidst large decorative swirls. Height: 30.2 cm, width: 21.5 cm.

At the beginning of this year I acquired a copy of

The Universal Songster from the bookseller Stephen Foster, Fosters’ Bookshop, 183 Chiswick High Road, London W4.

The Universal songster, or, Museum of mirth : forming the most complete, extensive, and valuable collection of ancient and modern songs in the English language : with a copious and classified index which will, under its various heads, refer the reader to the following descriptions of songs—viz. ancient, amatory, bacchanalian, comic (English), Dibdins’ miscellaneous, duets, trios, glees, chorusses, Irish, Jews, Masonic, military, naval, Scotch, sentimental, sporting, Welsh, Yorkshire, etc.—3 vols.—London: John Fairburn, 1825.

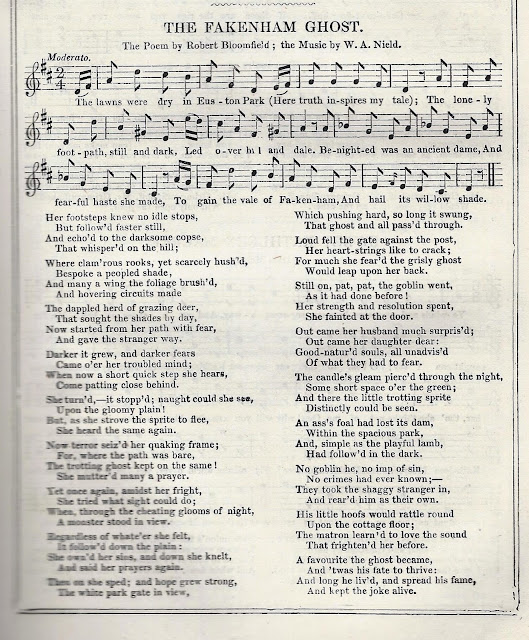

The volumes include three etched frontispieces by Cruikshank and 84 wood-engravings, of which 24 are after George Cruikshank, and 57 after his brother Robert. My three volumes have been recently rebound by Maltby’s of Oxford in quarter brown morocco, cloth boards, with gilt lettering. I think it would be almost impossible to find clean copies in the original publisher’s cloth—these books were read and reread. The books contain the texts only of popular “songs of the people” and have, as their title-pages reveal, an idiosyncratic classification system for the songs included. There are six times as many Irish songs as Jewish, and four times as many Scotch as Jewish, and twice as many Jewish as Welsh. As one might expect, the Irish and Jewish songs are filled with coarse ethnic stereotypes; the Scotch and Welsh are not. The songs by Bloomfield included are variously amatory, sentimental, and Scotch. The Universal Songster was reprinted several times throughout the nineteenth century.

Between the 1790s and the 1850s a vast output of chapbooks and songsters was issued under the imprint of the London printer-publisher John Fairburn, one of a dynasty of Fairburns, many of them named John. The family bookshop was initially situated at 146 Minories, close to Tower Hill, but in 1812, John Fairburn senior opened additional premises on the other side of the City in a court off Ludgate. The area was peppered with booksellers spreading west between Paternoster Row and Fleet Street. Fairburn notably employed members of the Cruikshank family of artists as illustrators and caricaturists. Thackeray, in an essay on George Cruikshank, remembered

… walks through Fleet Street, to vanish abruptly down Fairburn’s passage, and there make one at his ‘charming gratis’ exhibition. There used to be a crowd round the window in those days, of grinning good-natured mechanics, who spelt the songs, and spoke then out for the benefit of the company, and who received the points of humour with a general sympathizing roar. (6)

One is tempted to imagine Bloomfield in his way to or from the West End making a detour past Fairburn’s window.

A songster is an anthology of secular song lyrics, popular, traditional, or topical, and typically designed to fit into the pocket. Some later songsters carried melody lines but most songsters are text only. The use of musical notation was limited by the page size and the fact that it had to be engraved rather than set from moveable type.

Fairburn Senr’s Laughable Song Book for 1812 has 33 pages, words only, including Bloomfield’s “Love’s Holiday”. So the

Universal Songster’s substantial volumes are exceptional. According to Fairburn, the three volumes form: “... the most complete, extensive and valuable collection of ancient and modern songs in the English language ... ”. The public wanted the words to the most popular songs and it was only natural that these would end up in a printed form. There really wasn’t a popular music industry as such at this time—no enforceable copyright ownership in songs and no one could prevent the printing of a song in a newspaper or book. Bloomfield would have received no payment for the pirating of his poems in songsters.

In some ways songsters follow on from the broadside ballad sheets, which were the main printed carrier of songs in the eighteenth century. But in terms of both printed format and means of distribution they relate to the chapbook, still going strong in the early nineteenth century, and its sub-genre, the “garland”.

Chapbooks were small, inexpensive eight-page booklets were often illustrated with woodcuts and printed on coarse paper. They were distributed by traveling “chapmen” who sold the books at markets and door-to-door in rural areas. Chapbooks (called garlands if they included songs) were a popular form of entertainment in the 18th and early 19th centuries and the principal way that ordinary people encountered songs and poetry. Chapbooks and garlands would have provided the young Robert Bloomfield with reading matter and a first introduction to poetry.

Costing a penny for eight small pages (the first given over to a title-page adorned with a crudely-cut and often irrelevant woodcut), a garland would contain the words—but not the music—of perhaps half-a-dozen songs, covering a wide variety of subjects and appealing to a number of levels of taste; a sentimental love lyric in eighteenth-century cliché, a humorous poem describing an Irishman’s adventures in London, a poem in praise of the Battle of the Nile, a sailor’s lament at his absence from home, and so forth. Towards the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth an enormous number of song-collections designed for the cheapest market were published, the eight-page garland growing into the slightly more extensive songster.

These garlands and songsters throw an interesting light on the popular taste of the time. They were aimed at both genteel and vulgar audiences, and appeared in many thousands of printings between the mid-eighteenth century and the end of the nineteenth with occasional appearances even in the twentieth century. Here’s a song from the Universal Songster that catches the flavour of the period and mentions several extremely popular songs.

The Ballad Seller

Here are catches, songs and glees,

Some are twenty for a penny,

You shall have whatever you please,

Take your choice for here are many,

Hear is ‘Nan of Glo’ster-Green’,

Here’s ‘Lily Of The Valley’,

Here is ‘Kate of Aberdeen’,

Here is ‘Sally In Our Alley’.

Here is ‘Mary’s Dream’ ‘Poor Jack’,

Here’s ‘The Tinker and The Tailor’,

Here’s ‘Bow Wow’ and ‘Paddy Whack’,

‘Tally-Ho’ ‘The Hardy Sailor’,

Here’s ‘Dick Dook’ ‘The Heart Blade’,

‘Captain Wattle’ and ‘The Grinder’,

And I’ve got ‘The Country Maid’,

Confound me though, if I can find her.

Drinking songs, too here abound,

‘Toby Philpot’ ‘Fill The Glasses’

And, ‘Here’s A Health To All Good Lasses’,

Here’s ‘Come, Let Me Dance & Sing’,

And, What’s better far than any finer,

Here’s ‘God Save Great George Our King’

‘Hearts of Oak’ and ‘Rule Britannia’.

The Universal Songster contains ten poems by Bloomfield:

Vol. I.

page 65: THE WOODLAND HALLO! (Bloomfield.)

page 89: WELCOME SILENCE, WELCOME PEACE. (R. Bloomfield.)

page 174: ROSAMOND’S SONG OF HOPE. (Bloomfield.)

Vol. II.

page 28: HAIL, MAY! LOVELY MAY. (R. Bloomfield.)

page 106: ROSY HANNAH IS MY OWN. (R. Bloomfield.)

page 329: OLD WINTER COMES ON WITH A FROWN. (Bloomfield.)

Vol. III.

page 24: HERE FIRST I MET THE LOVELY MAID (R. Bloomfield.)

page 88: THE PLOUGHMAN’S COURTSHIP (R. Bloomfield.)

page 218: LOVE’S HOLIDAY (R. Bloomfield.)

page 295: HOME IS SO SWEET, AND MY MOGGY’S SO KIND. (Bloomfield.)

The implication must be that all ten poems are well-known songs, and readers of the Universal Songster only need a reminder of the words.

The songs in detail:

THE WOODLAND HALLO!

Category: Amatory.

Composer: Nina d’Aubigny von Engelbrunner (London: Vollweiler, 1806).

On 2 January 1807 the following advertisement was printed on the first page of The Morning Post:

NEW MUSIC, by Miss Nina d’Aubigny Von Engelbrunner, Author of The Essay on Harmony, Letters on the Art of Singing, &c.—This Day is published, in a style particularly elegant and new, Bloomfield’s Woodland Hallo, composed by Miss Nina d’Aubigny Von Engelbrunner, price 1s. Also, a Collection of Songs with English and German Words, by the same Composer. ... Printed on stone and sold for G. J. Vollweiler, at his Poliautographic Press, No. 9, Buckingham-place, Fitzroy-square …

WELCOME SILENCE WELCOME PEACE

Category: Sentimental.

No composer known.

First published in Wild Flowers (1806) as “Love of the Country”.

ROSAMOND’S SONG OF HOPE

Category: Sentimental.

Composed by Isaac Bloomfield.

First published in May Day with the Muses (1822), page 67.

HAIL MAY! LOVELY MAY

Category: Amatory.

No composer known.

First line: Hail, May! lovely May! how replenish’d my pails!

First published in the Preface to The Farmer’s Boy (1801), page xi, as “The Milk-maid on the first of May”.

ROSY HANNAH IS MY OWN

Category: Amatory.

Settings by both Isaac Bloomfield and James Hook.

First published in Rural tales, ballads, and songs (1802), page 96, as “Rosy Hannah”.

OLD WINTER COMES ON WITH A FROWN

Category: Sentimental.

Setting composed by James Hook.

First line: Dear boy, throw that icicle down,

First published in Rural tales, ballads, and songs (1802), page 104, as “Winter Song”.

HERE FIRST I MET THE LOVELY MAID

Category: Amatory.

No composer known.

First line: Here first I met the lovely maid.

“Air” from Hazelwood-Hall (1823).

As evidence of its continued popularity, later published in The Crotchet; or the Songster and Toast-master's companion: consisting of several thousand favourite songs & popular toasts containing all that is requisite to enable any one to take a part in social and convivial meetings (London: published for the booksellers, 1854), page 178.

THE PLOUGHMAN’S COURTSHIP

Category: Amatory.

No composer known.

First line: Down Abner sate, with glowing heart,

I found the following in Tammas Bodkin: or the humours of a Scottish tailor, a collection of humorous essays in Scots vernacular.

It bein’ Andro’s prerogative to fix upon the individual wha was to sing the neist sang, he pitched upon Miss Swingletree, whase musical reputation was scarcely inferior to that o’ her respected faither. Hoosondever, she beggit to be excused on the grund that she had a sair throat, an’ was as hearse as a crowpie, but she wad ask Mr Hoggie to ack as her substitute, an’ wad feel particularly flattered if he wad favour the company by singin’ “The Ploughman’s courtship,” whilk he furthwith proceeded to do, the haill assembly joinin’ in the chorus, snappin’ their fingers an’ stampin’ on the floor wi’ their tackety shoon like very mad. (362)

Could this be Bloomfield’s poem, now absorbed into folk-song? There is another song of the same title (first line: “When first a-courting I did go”), printed in a Scottish chapbook, which might be considered a more likely candidate. But the chapbook (and the song) is known only in a single copy and no tune has so far been traced. I would like to think that Bloomfield has another shadowy existence as a Scottish poet.

LOVE’S HOLIDAY

Category: Amatory.

Setting composed by James Hook.

First line: Thy Fav’rite bird is soaring still,

Earlier issued by Fairburn in Fairburn Senr’s Laughable Song Book for 1812. With note “Written by Robert Bloomfield, composed by Mr. Hook, and sung by Master Hopkins, with universal applause; at Vauxhall Gardens. Season 1811.”

HOME IS SO SWEET AND MY MOGGY’S SO KIND

Category: Scotch.

Settings by both Isaac Bloomfield and by Robert himself, but presently untraced.

Extract from Bloomfield’s “Song for a Highland Drover returning from England”.

Beginning with the third verse: O Tweed! gentle Tweed, as I pass your green vales.

Verse ends: For home is so sweet, and my Maggy so kind.

First published in Rural tales, ballads, and songs (1802), page 97. Why “Maggy” should be changed to “Moggy” just baffles me.

Sources and further reading

John Fairburn.—Fairburn Senr’s Laughable Song Book for 1812.—London: John Fairburn, 1811.

Michael Kassler, “Vollweiler’s Introduction of Music Lithography to England”, chapter 9 of Michael Kassler, ed., The music trade in Georgian England.—Farnham: Ashgate, 2011.

The Ploughman’s courtship. To which are added, Johnny Coup’s defeat, and The Distressed lover.—Falkirk: T. Johnston, printer, [181-?].

An apparently unique surviving copy in Glasgow University Special Collections.

Tammas Bodkin: or the humours of a Scottish tailor.—Edinburgh: John Menzies, 1864.

A collection of humorous essays in broad Scots, published anonymously, though by William Duncan Latto.

William Makepeace Thackeray.—Essay on the genius of George Cruikshank. With numerous illustrations of his works.—London: Henry Hooper, 1840.

From the Westminster Review, No. LXVI.